When a devastating earthquake struck Morocco, claiming over 2,900 lives, King Mohammed VI found himself far from his kingdom, in Paris, where he often spends a significant portion of his time.

It took him nearly a day to return to Morocco and issue his sole public statement—a brief communiqué. Subsequently, television footage showed him chairing a cabinet meeting, yet without accompanying sound.

On Tuesday, he visited a hospital and donated blood. However, his limited visibility and silence, compounded by the government’s response to the earthquake, have drawn criticism. Some argue that officials seem immobilized, seemingly waiting for the king’s authorization to take action.

Moroccan authorities contend that they are effectively managing the crisis and will seek assistance as necessary, asserting that the king has been guiding the response from the outset.

King Mohammed VI, who turned 60 on August 21, holds the distinction of being the wealthiest and most powerful individual in Morocco. Constitutionally, he serves as both the head of the armed forces and, controversially in Islamic terms, the Commander of the Faithful, overseeing religious matters.

As the head of state, he presides over a constitutional monarchy, a managed semi-democracy where substantial power is wielded by advisers and ministers, most of whom are close associates from his high school days. However, his approval remains pivotal.

Furthermore, Moroccans close to the government suggest that the king has become less accessible and increasingly linked to a younger, German-born Moroccan mixed martial arts fighter, Abubakr Abu Azaitar, whom he met around the time of his divorce in 2018. Speculation abounds that Abu Azaitar may be driving a wedge between the king and his advisers.

Nonetheless, many aspects of life within the royal palace and details concerning the king, including his health, remain shrouded in mystery. Despite a history of health issues, such as an irregular heart rate and acute viral pneumonia, there is no official information available about his current condition.

In Morocco, where the media is tightly controlled and the king has never held a news conference or given an unscripted interview for years, rumors often circulate, fueled by personal and political agendas.

Morocco is widely regarded as a success story in North Africa, known for its comparative openness, stability, and appeal to industry and tourism. Additionally, it has been a reliable partner to the United States and the West in counterterrorism efforts, and it recognized Israel in 2020.

Critically, King Mohammed VI adeptly navigated the turbulence of the Arab Spring over a decade ago, partly through domestic and political changes that adopted a more modern, democratic tone. Moreover, his government aggressively countered radical Islamist politics and terrorism following bomb attacks in 2003.

However, the pervasive ambiguity surrounding the king’s authority and life, akin to the situation in Thailand, has marginally eroded Morocco’s reputation.

Fouad Abdelmoumni, a Moroccan economist who criticized the sluggish official response to the earthquake, expressed his belief that the government appears reluctant to take action until the king grants authorization. He noted that this pattern mirrored the 2004 earthquake response, when officials only arrived in devastated villages after the king’s visit.

Mr. Abdelmoumni indicated that “it seems that all the king’s entourage is very very unhappy with the time he spends with the Azaitars, the authority he gives them, their behavior toward society and elites and the image this creates around the king and the state.”

However, what remains evident is that “the king likes the Azaitars a lot, and all the others are unhappy,” he added. “They all agree ‘we have to be all united against Abu Azaitar.'”

Morocco maintains a conservative society where the monarchy enjoys immense respect, despite stark disparities between the elite and the impoverished masses. In this context, the lives of the king, his entourage, and his 20-year-old son and heir, Moulay Hassan, are cloaked in official silence.

Open criticism of the king is rare due to severe penalties, and political opposition has been marginalized. Those who have left the country often feel freer to voice their opinions.

Nonetheless, Morocco ranks 144th in the World Press Freedom Index, indicating minimal media freedom.

Just recently, Moroccan blogger Saeed Boukayoud was sentenced to five years in prison for Facebook posts deemed critical of the king’s policies related to Israel. His lawyer, Hassan al-Sunni, stated that these posts “denounced normalization with Israel in a way that could be interpreted as criticism of the king.”

In contrast to his father, King Hassan II, who had authoritative but diverse advisers, King Mohammed VI operates within a more insular sphere, enriched both personally and through his courtiers. This shift has raised concerns about the underdevelopment of Morocco’s institutions and the misallocation of resources.

King Mohammed VI ascended the throne in 1999 and, in a rare interview a year later with Time magazine, positioned himself as a reformer aiming to address “poverty, misery, illiteracy.” However, he acknowledged that “whatever I do, it will never be good enough for Morocco.”

Despite ruling alongside individuals selected from his high school circle, King Mohammed VI instituted substantial changes in conservative Morocco. He pardoned numerous political prisoners, revised family law to raise the marriage age from 15 to 18 (with exceptions allowed by local judges), and introduced measures to enhance gender equality and facilitate legal divorce proceedings.

However, challenges persist, including the legalization of polygamy with the consent of the first wife, alongside prohibitions on homosexuality and extramarital relations.

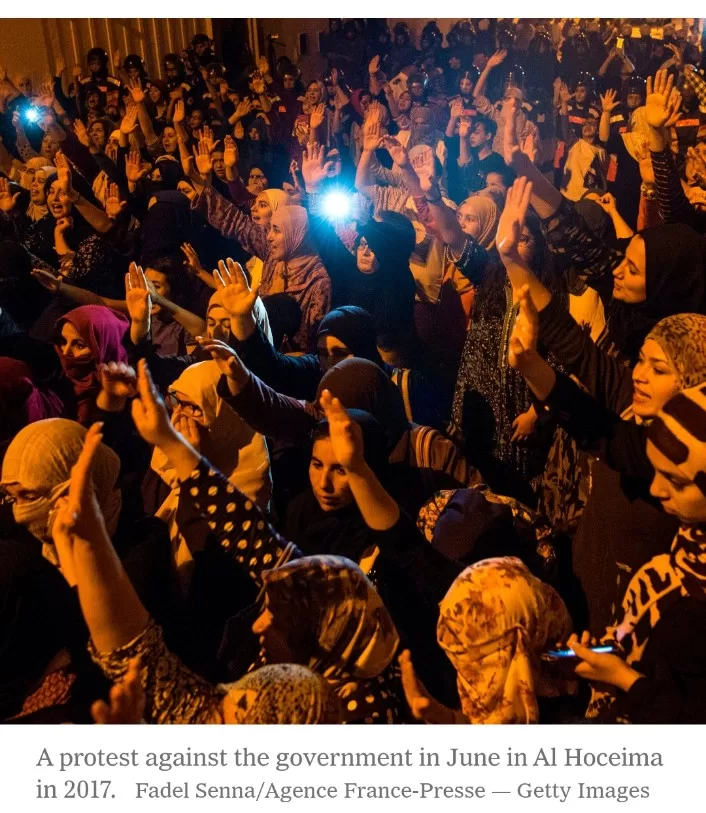

The king navigated the Arab Spring’s discontent by amending the Constitution in 2011 and permitting an Islamic party to govern after winning elections. Subsequent protests in 2011 and 2016-2017 were met with government repression, particularly targeting the media.

Moreover, urban youth unemployment, a significant catalyst for the Arab Spring across the region, currently afflicts Morocco to a more severe extent.

While the Constitution was modified in 2011 to allocate greater power to Parliament, its implementation remains symbolic rather than practical, with notable deficiencies in institutional mechanisms and checks and balances that safeguard individual and minority rights.

Government spokesperson Mustapha Baitas has dismissed criticism of the government’s response to the earthquake and rumors surrounding the king as unsubstantiated claims by the foreign press. In a social media video, he asserted that authorities swiftly intervened following the earthquake, guided by the king’s instructions.

François Soudan, editor in chief of Jeune Afrique, defended the king before his 60th birthday in August against articles in the Economist’s 1843 magazine and the Times of London. He claimed these pieces relied on unfounded rumors and were authored by individuals lacking access to the king or the palace.

Soudan praised the king’s adaptability and close rapport with the Moroccan people, noting that “Mor

Source AP