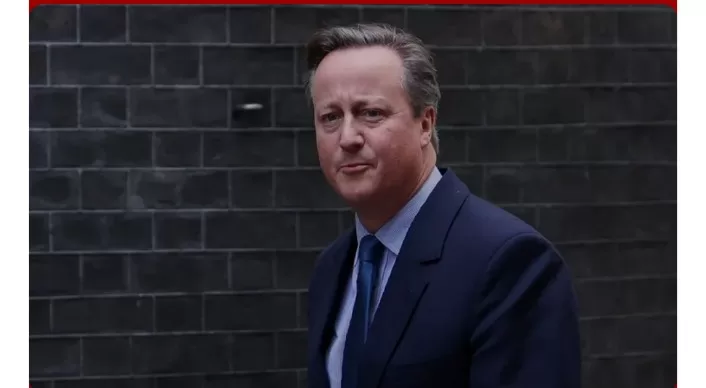

The recent appointment of former Prime Minister David Cameron to the position of Foreign Secretary has sparked intrigue and raised eyebrows in political circles, given his retirement from the House of Commons seven years ago. The unusual move has prompted a closer examination of the mechanisms that enable such a return to a top ministerial role.

Cameron’s return is facilitated by his immediate elevation to a life peerage, as announced by Downing Street. This grants him a seat in the House of Lords, providing the constitutional foundation for assuming a ministerial role despite not being a current member of the Commons. While it is theoretically possible to be appointed a minister without parliamentary membership, practical considerations often lead to such individuals finding a place in the Lords.

In the realm of contemporary UK politics, it is customary for most government departments to have ministers from the Lords, typically occupying junior positions. However, cabinet members from the upper house are relatively rare, with the leader of the Lords, currently Lord True, being the primary exception. Notably, former Culture Secretary Nicky Morgan continued in her role for several months under Boris Johnson after transitioning from MP to peer in the aftermath of the 2019 general election.

While the appointment of cabinet ministers from the Lords is infrequent, historical instances provide context. The most notable parallel to Cameron’s situation is the appointment of Peter Carington, a hereditary peer, as Margaret Thatcher’s Foreign Secretary from 1979 to 1982. Another comparable case occurred in 2008 when Gordon Brown appointed Peter Mandelson, who had resigned from parliament four years earlier, to the House of Lords and made him Business Secretary.

Serving as a cabinet minister in the Lords presents its own set of challenges, given the differences in the functioning of the upper house compared to the Commons. Cabinet members in the Lords undergo scrutiny, although the lack of routine updates and urgent questions necessitates a delegation of daily responsibilities to a designated subordinate. In Cameron’s case, this responsibility falls on Andrew Mitchell, the current International Development Minister.

The return of Cameron to a prominent ministerial role will not shield him from full scrutiny. While the Lords may project a more composed atmosphere than the Commons, the diverse expertise among peers can make ministerial questions a nuanced experience. As the Foreign Secretary, Cameron will also be subjected to media interviews, opening the door for journalists to delve into his performance, including contentious matters like the Greensill lobbying scandal and his record as prime minister.

The unprecedented nature of Cameron’s return to government brings into focus the evolving dynamics of parliamentary norms and the nuanced interplay between the executive and legislative branches.