The intertwining of art, fame, and fortune within the East India Company’s operations in India stands as a stark reminder of colonial predation driven by economic ambitions. This exploitative engagement reveals a distressing narrative where cultural treasures were harnessed as tools of financial gain, leaving an indelible mark on India’s heritage.

Art as Plunder:

The East India Company’s pursuit of art was far from a benign endeavor. The seizure of artistic treasures bore testimony to the voracious quest for wealth. Notably, the Company’s annexation of the Peacock Throne of Shah Jahan and the subsequent looting of the Mughal treasury in 1739 during Nadir Shah’s invasion exemplify this nefarious underbelly. These acts stripped India of its cultural relics and enriched foreign coffers.

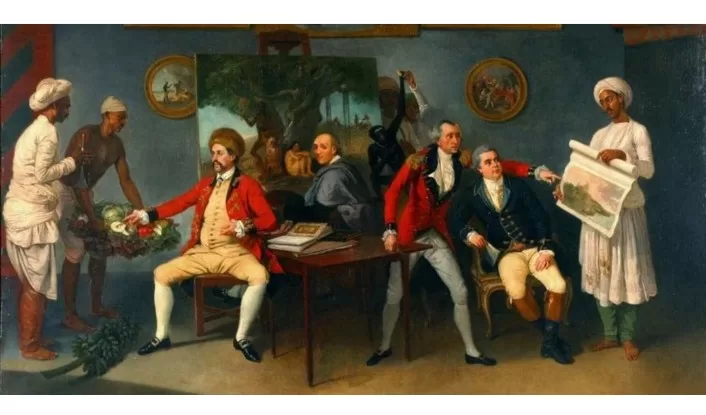

Profits from Patronage:

By patronizing artists, the East India Company facilitated the propagation of their agenda. Artists like Thomas and William Daniell were commissioned to romanticize India’s landscapes, magnifying the Company’s benevolence while concealing their exploitative endeavors. This duplicitous portrayal furthered the Company’s interests while manipulating artistic narratives.

Economic Windfalls:

The figures behind the East India Company’s economic exploits during this period are staggering. In the mid-18th century, their revenues touched £2 million annually. By the late 1700s, they amassed £3.5 million each year. The fortunes acquired were largely built on coercive trade practices, exploitative taxation, and resource depletion, with art serving as both spoils and currency.

Human Tragedies:

The Bengal Famine of 1770 remains an emblem of the Company’s ruthless pursuit of profit. While art, fame, and fortune flourished for the Company, millions of Indians perished in the famine. The Company’s tax policies, coupled with their rapacious looting of India’s resources, contributed to a humanitarian crisis that starkly contrasts with their affluence.

Plunder of Precious Gems:

The infamous Koh-i-Noor diamond serves as an epitome of the Company’s avaricious grasp. It was appropriated through the Treaty of Lahore in 1849, symbolizing the Company’s insatiable lust for precious gems. This exploitation, far from being an isolated incident, underscores a systemic pattern of resource expropriation.

Cultural Erosion:

Through their pursuit of art, the Company often acted as cultural despoilers. Treasures like the Amravati Stupa panels, seized in the 19th century, are now housed in British museums. This act of detachment from cultural context and history stands as a testament to the Company’s insensitivity to the intrinsic value of art.

Legacy of Exploitation:

The ramifications of the East India Company’s exploitative art-centric endeavors are undeniable. India’s cultural heritage has been marred by the loss of innumerable artifacts and historical relics. These scars endure as painful reminders of a past marred by colonial rapacity.

In summation, the East India Company’s orchestration of art, fame, and fortune to further their economic objectives represents a disheartening chapter in history. The statistical data, the plundered art, and the human suffering endured by India lay bare the deep-rooted exploitation that marked this period. As we reflect upon this chapter, it is incumbent upon us to recognize the multifaceted dimensions of colonial predation and the lasting impact it has left on India’s collective memory.